Cake Zine friends,

For many, baking is a hobby, an act of care or escape after a long day sitting in front of a computer. But for those who do it professionally, it’s intensely physical labor. Not just the early mornings or the colossal bags of flour, but the slow, relentless wear on the body—wrists strained from piping, knees pulsing from hours on concrete, sciatic nerves wrecked after countless shifts at the bench. This week in the newsletter, we’re sharing an excerpt from our new issue Daily Bread by Dayna Evans, baker and co-owner of Downtime Bakery in Philly. In it, she unpacks the physical toll of a profession built on repetition, endurance, and the quiet expectation that pain is part of the job.

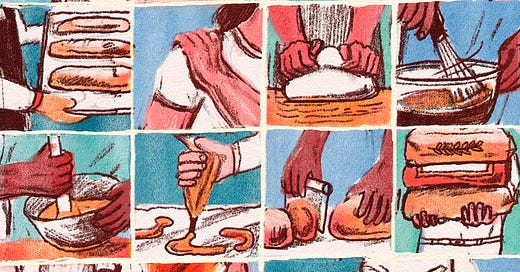

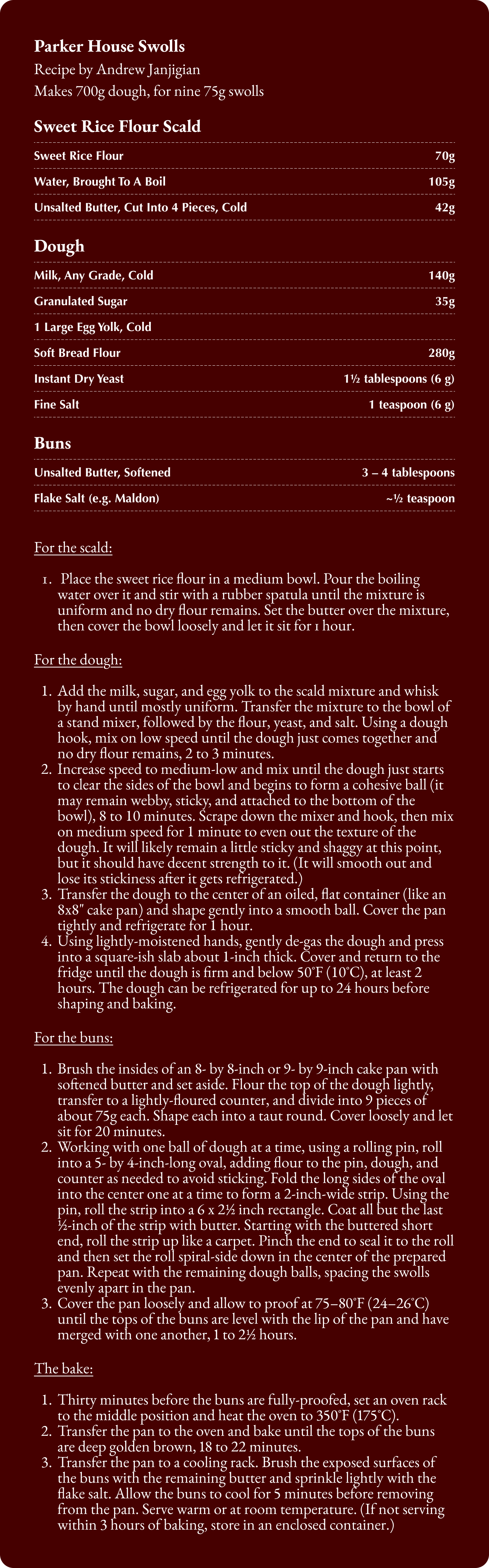

Alongside the essay, we have a recipe from Andrew Janjigian (aka Wordloaf, one of our favorite baking newsletters) for his Parker House “swolls”—a plush, buttery, shokupan-inspired take on the classic roll that’s easy to make and eat.

The Baker’s Body

By Dayna Evans

My wrists were the first body part to file a formal complaint. At the South Philly pastry shop where I worked, I noticed I was struggling to summon the grip strength to fully express the contents of a piping bag. I’d feel a cautionary tingling emanate from my fingers all the way up my forearm while I forced cream cheese fillings or too-cold frangipane into fragile pastries. Something was wrong.

In the mornings, commuting to work before daybreak, I’d shake both of my hands furiously in front of my steering wheel, trying to release the ceaseless prickle that came from slowly advancing carpal tunnel. At night, I’d wear a wrist brace to sleep: first, on my right hand; then, when I was inevitably woken up by the pain and numbness in my other, I would switch the brace to my left. It was a ritual I’d complete with a pious sort of pragmatism, outweighing the fact I was half-asleep and barely functioning. Still, my varying degrees of alertness didn’t matter. Sitting in the crowd at a bike polo tournament one afternoon after work, I asked my friend, a doctor, if surgery was in my future. She put it plainly: “They’ll go in and snip the sheath that holds your median nerve.” I shuddered. Surely, they wouldn’t do that. My body would bounce back. I was young, agile, optimistic. It was hard to accept the hazards of a craft I loved so much.

At age thirty-six, my body was familiar to me in the way many people know, as a physical manifestation of a psychological burden. I reasoned with it, yearned to change it, and gave it hell. But for all my commonplace frustration, I didn’t nurture it. I didn’t understand it.

There were small things I noticed almost immediately when I began working in bakeries in my early thirties and eventually running my own: My calves cramped and felt tight, swollen. I would check in with my posture at the bench where I shape bread and notice how I had been leaning into it—onto it, even—with my belly, making a quiet convex curve. I was both static and active for hours at a time, exhausted in ways I had never previously identified or felt. My brain was always moving, faster and faster, but my body bore the strain. It hurt in new ways. I was used to having my mind talk to me, tell me what I needed and how to fix it. I had never listened to my body before. I had never heard it talking. Rest, it said. Stretch, it said. Take care.

When I ran a bakery from the basement of my home, before the brick-and-mortar I run with my partner opened in the fall of 2024, I would try to count the number of times I’d run up and down the steps after 4 or 5 a.m. Load the sourdough downstairs, shape the brioche upstairs, set a timer, repeat. Take cookies out upstairs, put baguettes in downstairs, repeat. It was always too difficult to keep track of the steps, because while my body moved fast, my brain was tripping over itself to keep up. From years of working as a writer, I had been taught to believe that my brain was more important in the divide between mind and body. So I shushed my body. I ignored its needs. The pulsing in my knees persisted.

The pain then showed up in my right thigh. Running had long been my preferred form of cardio exercise and emotional release, but I had so rarely considered that I might have to choose between baking and running, especially after days of standing on my feet for hours on end left me feeling worn through. I enjoyed the mental break that came from running after a bakery shift, a necessary change of scenery and a way to shatter the static hyper-focus that comes with bakery production work. But my spine had begun compressing on my sciatic nerve, an orthopedist told me, and so on trail runs, I would feel that I was dragging one leg behind me, as a lightning bolt of pain jackknifed up the back of my thigh. I went to cupping sessions with a sweet and happy physical therapist. I commiserated with another baker about doing rounds of clamshell exercises “until failure” every night before bed. She kept up the exercises more consistently than me, and I felt she was fitter and more committed to the job because of it.

Many bakers told me they have not yet found a way to maintain a proper physical balance in this chosen path of theirs, one that doesn’t take such a toll on our bodies and allows for longevity in our craft. One bread baker, Claire Ogilvie of Philly’s Kettle Black Bakery, told me that she feels “stronger and weaker all at once,” after long hours mixing, dividing, shaping, and baking dough into existence. She said she has “new muscles I never knew before,” but also permanent changes that she’ll never come back from, like the sciatica that plagued me. Bread bakers often claim that the work itself is our exercise: moving fifty-pound bags of flour, coil folding twenty-five-pound tubs of dough, sliding heavy breads out of a hot oven with seamless ease. That is, until we can’t do either anymore. When we’re young, or able, or both, we take on the weight of the flour bags as a challenge, one passed down from approving mentors and bosses. The shame that’s felt when these tasks seem too hard or too painful is a dated, persistent callback to the masculine origins of the craft. “My thesis,” Sara May, a Philly-based recipe developer and baker, told me, “is that there is no retirement plan in this community.”

For some, bread baking comes after retirement. For Joe Bowie, an artisan baker and dance educator in Illinois, it took years to realize the correlation between his decades of experience as a dancer and his later years as a baker. “As soon as I finished my last dance project, I started culinary school a week later,” Bowie, who is now sixty, told me. “And so I was like, ‘Now, I’m a baker—I was a dancer.’ I had thirty years of embodied knowledge, but I didn’t use it.” After over a decade as a production baker, Bowie shut off the part of his brain that told him to focus on how his body felt. The bread was always more important than the baker.

Dancing and baking can both cause repetitive stress syndrome, Bowie said, describing how the shaping bench is like a ballet bar. Dancers learn to plié and jeté in the same consistent motion, just like bakers learn to move forearms and wrists while shaping loaves. Each day requires repeating the same physical tasks in order to create a consistent, artisan product from doughs that vary wildly by the temperatures, environments, flours, and hands involved. Your own touch influences each loaf: from the mix to the shape to the score to the bake. Every task is both highly individualized and anonymous at once, so if the baker is not physically available to the task, the bread suffers, too.

“I think that it’s inherently choreographic, the movements through bakeries,” Bowie said. “I wish that those who own bakeries or oversee bakers would really take the time to consider the bodies of the people working for them. There’s no way that a baker does not need a break, there’s just no way.”

Bowie brought up the work of Rudolf von Laban, an Austrian dancer and choreographer, who pioneered the idea of exertion and recuperation. “The idea of recuperation is not necessarily just lying flat on your back,” Bowie says. “The idea of recuperation is to disrupt what you’re doing, almost to intervene on what might be a pattern in your body. So if you’re staring at a bench all day long, the intervention could simply be going outside and looking at the sky.”

While bread’s simple process has stayed the same for centuries, bakers have started demanding more recognition of its inherent hazards. The mandatory breaks, the team stretching, the twenty-five-pound bags of flour versus the fifty-pound bags. The all-important saving grace of the squishy anti-fatigue mat.

At the pastry shop where I worked in South Philly, rotating members of our team would interject in the middle of the morning bake: “Has everyone stretched recently?” “Are we all drinking water?” “Is anyone hungry?” At another bakery where I staged in Portland, breaks were enforced with insistence by managers. No task was too important to put on hold for ten minutes. At our bakery, we take breaks, we talk to each other, we look out for each other.

In Jeffrey Hamelman’s seminal 2004 cookbook Bread, an entire chapter is devoted to how bakers use their bodies: “The baker is lucky, lucky indeed, to have this life of the hands,” Hamelman writes. The luck comes from our ability to understand and manipulate dough; to know what it should feel like when it is baked, when it is ready to display for consumers. In the forum for the Bread Bakers Guild of America, Hamelman kindly responded to my questions about how bakers take care of their bodies. Hamelman said that it is the intersection of the physical and the mental that makes bread-baking such a joy. “We bakers are always engaged in body and mind—and we are lucky for that (humans have evolved exactly for that combination). Imagine sitting in front of a computer for eight hours a day?” His point: Being in brain-forward jobs only denies your body, this other wonderful part of your specimen, its ability to express itself.

Years after I started learning to bake and figuring out what my body could handle, I began to notice another transitory effect of the work: I started to pay attention and appreciate, to feel pride in, this body of mine. It was no longer just a benign object over which my brain had power—it was its own entity, its own home, a singular and powerful piece of craftwork that I had no choice but to care for. I started surfing; I stopped drinking; I started seeing the change in strength as an extension of my love for baking bread. I wear compression socks at work now. I strength-train, run, and do yoga when I can. I have new ailments that come up and old ones that have abated. But I am aware of these changes, I don’t let pains go on for too long before I investigate them, care for them. I am careful with myself.

Dayna Evans is the head baker and co-owner of Downtime Bakery in Philadelphia, PA. When she has downtime, she likes to lie completely still on the hardwood floor for as long as her schedule allows.

Parker House “Swolls”

By Andrew Janjigian

This is my take on a Boston classic, the Parker House roll, made by flattening a round of dough, slathering it with butter, and folding it in half like a taco. I love the idea of them, but in practice find them kind of boring, especially since they’re not baked snuggled together in a pan like the sorts of dinner rolls I love. Instead, I make Parker House swolls, using a fluffy shokupan dough, shaped just shokupan, except the spirals sit face-up in the pan. They are very, very good—the sort of thing you can inhale half a pan’s worth before you realize it. And they are easy-peasy to make, and not at all hard on the baker’s body (save all the butter they contain).

Notes from Andrew:

• Sweet (mochi/glutinous) rice flour is available in Asian markets, some supermarkets, or online. Bob's Red Mill or Mochiko are both excellent brands. Do not use another type of rice flour.

• If you cannot find sweet rice flour, you can use the same bread flour you use for the dough instead. In that case, use an alternative approach to making the scald: Combine the flour and cold water in a microwave-safe medium bowl. Cover and microwave on full power for 30 seconds at a time, stirring after each, until thickened, 3 to 5 minutes total.

• The ideal “soft bread flour” is a high-protein all-purpose flour, like King Arthur’s (the one in the red bag). If unavailable, use bread flour.

• I like to chill my doughs in flat, sealable containers (like lidded metal cake pans), because it speeds up chilling and allows the dough to rest in a flat slab, which makes dividing easy.

• The swolls can be made in an 8x8-inch or 9x9-inch cake pan; an 8x8 will yield slightly taller rolls.

I recently sold my bakery, in large part because my body just couldn’t take it anymore. Thank you for naming this and suggesting some more sustainable ways forward.

So grateful for our bakers! And I’m definitely going to try making these rolls - they look amazing!